Should Johnny Paul Penry Die?

He plunged a pair of scissors into Pamela Carpenter’s chest, raped her, and stomped her to death. His IQ is estimated at anywhere from 51 to 63. Should that exempt him from the death penalty? This month the Supreme Court will provide only part of the answer.

By Alex Prud’homme; additional reporting by Joanne Harrison; Photos by Jim Goldberg

JUST BEFORE THREE O’CLOCK LAST NOVEMBER 16, THE WARM afternoon and creeping sense of inevitability in Huntsville, Texas, were suddenly interrupted by the shrill sound of ringing cell phones. ‘wen people all over this small town-women, mostly-began to cry out. Some cried in relief, others in anguish.

JUST BEFORE THREE O’CLOCK LAST NOVEMBER 16, THE WARM afternoon and creeping sense of inevitability in Huntsville, Texas, were suddenly interrupted by the shrill sound of ringing cell phones. ‘wen people all over this small town-women, mostly-began to cry out. Some cried in relief, others in anguish.

At 6 p.m. that evening, 44-year-old Johnny Paul Penry was scheduled to be strapped to a gurney at the Walls Unit, an old red brick prison building known as “the death house,” and executed by lethal injection. He’d been convicted for the brutal 1979 rape and murder of Pamela Moseley Carpenter, a 22- year-old housewife in the East Texas town of Livingston. But Penry was no ordinary convict. He had an IQ somewhere between 51 and 63 (the intelligence level of a six-or seven-year old) and had been horribly abused as a child. He still liked to draw with crayons, and he believed in Santa Claus. As a result Penry was at the center of a raging controversy: Should the mentally retarded be put to death for capital crimes?

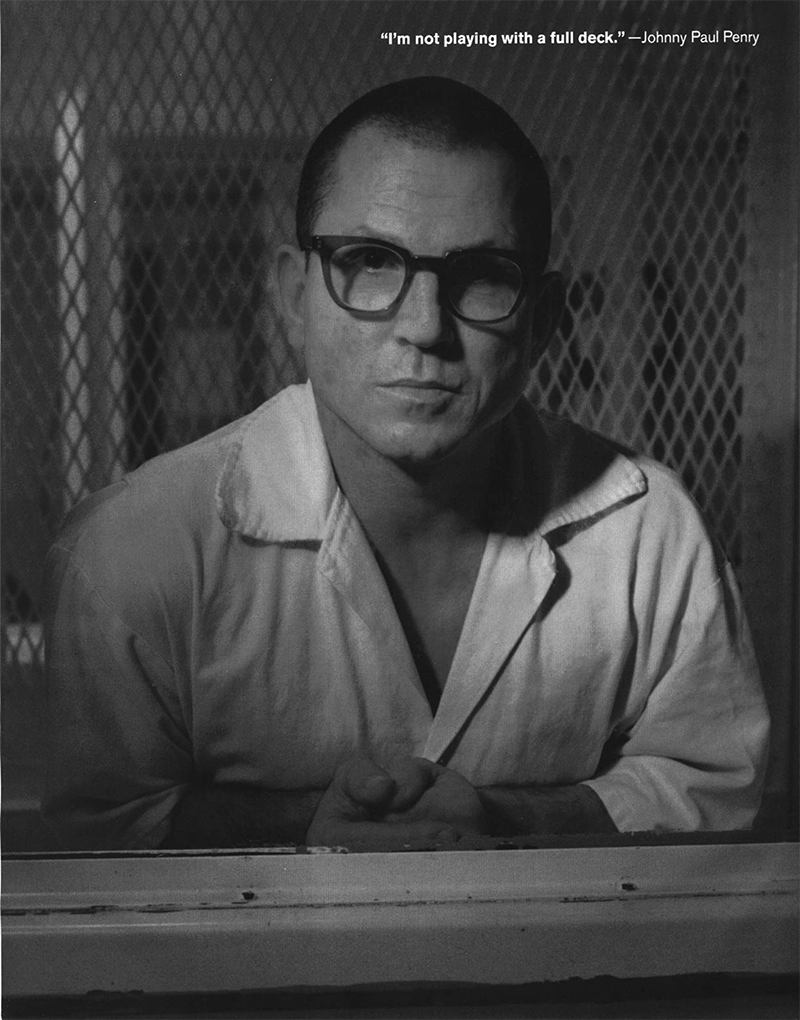

All afternoon Huntsville had swelled into a kind of macabre carnival filled with pro- and anti-death penalty protesters and TV news cameras. Inside a holding cell, Johnny Paul Penry – a man of medium height with black brush-cut hair and wide-set eyes behind thick black-framed glasses-nervously wolfed down the pickles and cheese left by the previous tenant, who had been executed. “Execution isn’t so simple to explain to someone like Johnny,” recalls Father Stephen Walsh, Penry’s spiritual adviser. “We talked it over in terms of sleeping, and he eventually calmed down.”

It seemed inevitable that Penry would soon become the third inmate executed in Texas that week-and the 38th that year.

If the Supreme Court agrees with Texas, Penry could be executed within a matter of weeks. “People don’t want to hear it, but Mr. Penry will be gone soon,” predicts William ”Rusty” Hubbarth, an attorney for Justice for All, a pro-death penalty and victims advocacy group. Anti-death penalty groups believe the case will be remanded back to Texas for a third trial. Furthermore Penry is not technically eligible for parole. Although the possibility of his walking free appears to be distant, the Moseley family is not reassured by that. “Who knows?” says Ellen May. “Governors change, laws change, his sentence could be commuted-anything could happen over Lime. It scares the living daylights out of me that he could walk out those doors.”

Although he declined to comment for this article, President George W. Bush has a long history with the Penry case. Last November, as governor of Texas, Bush was awaiting the Supreme Court’s ruling on the presidential election. He had run as a “compassionate conservative” and was being criticized for having overseen 150 executions, including at least three of mentally retarded prisoners, in six years-a new record. Indeed, a purportedly retarded inmate named Mario Marquez was executed on the morning of Bush’s gubernatorial inauguration in 1995. When the Supreme Court agreed to rehear the Penry case, it saved Bush from having to decide between granting Penry a reprieve and putting him to death.

In an odd twist, Penry’s sister Belinda Gonzales claims that President Bush is related to her family. For evidence she points to a detailed genealogy, self-published by a cousin, about the Bushes in America. Penry is certainly related to a Bush family, but it’s unlikely that family is the presidential Bushes. If a link exists, it is probably a shared ancestor in England centuries ago.

When l asked Penry about the president he said, “Mr. Bush, I think he’s a good man. But he made some mistakes. And he kept on making them and making them, and then he had earned him a new name: executioner! I he ain’t no Christian like he says.”

THIS PAST FEBRUARY I TALKED TO JOHNNY PAUL PENLY AT THE TERRELL UNIT, a modern prison only a few miles from the scene of Carpenter’s murder. Penry seemed eager to please, and he had a certain offbeat charm. But I found the conversation disconcerting.

Dressed in a white uniform, he smiled at me through the plexiglass and in a soft voice said, “Hello. What are we going to talk about today?”

Penry was shy at first: then he opened up. He pronounced his r’s as w’s-as when he said, ”my momma made me eat my own number two and dwink my own uwine.” His stories wandered, he was distracted by a buzzing noise in the ceiling, and he happily admitted he didn’t know the meaning of some of the words he used-“some people in here look at me like an outcast,” he said, “which I don’t know what that means.” He said he dreams about getting out of jail and getting a job as a busboy.

Yet Penry didn’t appear nearly as “retarded” as he has been portrayed in the reams of press coverage about his case. He was able to carry on a fairly normal conversation, could tell the correct time from his digital watch, and said he could read and write “a little bit.” Suddenly I understood why some prison guards and practically everyone I met in Livingston suspect his claim of retardation is disingenuous.

IT’S FAR FROM OVER. IN FACT, THE DEBATE OVER EXECUTING THE RETARDED is now one of the hottest legal topics in the nation. On March 26, in a surprise move, the Supreme Court decided it Would revisit whether such executions are constitutional. This fall the court will hear the case of Ernest McCarver, a convicted murderer with an IQ of 67; a ruling is expected in 2002. The turn about came exactly one day before the Supreme Court heard the case of Johnny Paul Penry for a rare second time. In Penry’s case the justices are looking at a narrower slice of the law: Did his murder trial jury receive enough inforation about Penry’s retardation to make a reasonable judgment about his fate? The court is scheduled to give its answer in June.

Whether the brouhaha over the Penry case caused the Supreme Court’s surprise move, only the justices know. But if the court does at some point rule against executing the retarded, it will be one of the most significant revisions in law since the reinstitution of the death penalty 25 years ago.

Like Nonna McCorvey, the woman called “Roe” in the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that legalized abortion, Penry has become the focus of a sharply divisive issue. As in Roe, large political forces are arrayed on either side, and the rhetoric is emotional. Indeed, Howard Cosell once called for Penry’s execution during a broadcast of Monday Night Football, and last year Bianca Jagger wrote an open letter on behalf of Penry for Amnesty International.

And like Nonna Mccorvey, Penry is a flawed icon. Although he’s been portrayed in the media as an amiable naif, he has a long history of violence, and there are questions about how retarded he actually is. Both times his case has gone to trial, juries have ruled unanimously to have him put to death.

“Penry is the wrong poster child for the issue of mental retardation,” says Ellen May. “He is not a sweet little boy.”

Then everyone’s cell phones began ringing; at virtually the last minute the United States Supreme Court had imposed a stay on Penry’s execution.

Ring. Kathy Puzone-one of Penry’s pro bono lawyers from Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, the powerful New York law firm famous for having defended Michael Milken – answered her cell phone with a shaky hand. “We got the stay!” she cried; overcome, she dropped the phone.

Ring. At a nearby hotel the family of Pamela Moseley Carpenter went into a collective state of shock. Rossie Moseley, Pam’s mother, crumpled to the floor. Jack Moseley, Pam’s father, a tough nails man spent his life working heavy equipment, broke down in tears. Ellen May, Pam’s niece, flung her cell phone across the room. Storming outside, she ran smack into a TV crew and unleashed her fury on it. “The Supreme Court had the stupid case for 30 days,” she says now. “So why did they wait until just three hours before the execution to tell us about the stay? It was one of the most devastating moments in my Life-right up there with Pam’s murder.”

Ring. When prison officials informed Penry of the stay, he shouted, “Thank God I’m alive!” Then he asked if he could still have his final meal: two cheeseburgers, french fries, soda, and cheesecake. The answer was no. The guards quickly returned Penry to dealh row at the Terrell Unit in Livingston. Penry irritated a fellow inn1ate named Gary Etheridge by asking, about 20 times in a row, “Hey Gary, is it okay to unpack my things now? Is it over?”

“I don’t know,” Etheridge answered, again and again.

“The Supreme Courc knows I’m not faking,” Penry said. “They know I’m not playing with a full deck. I am for real. And I thank them so much for that.”

Penry has denied committing the rape-murder of Pam Carpenter; he has also said he doesn’t remember it. When I asked hin, about the crime, he answered, “I’d better not get into that because my attorney told me not to.” Later, when I asked why he was in jail, he looked confused and replied, “I really can’t figure that out. I thought it was a dream, but it’s real.”

As I stood to leave he waved goodbye, and his grin reminded me of a smiley face. Then a TV crew began to set up lights and a camera for an intervievv. “Hello,” he said to the frosted-blond reporter. “Why are you here? What are we going to talk about?” I felt a twinge of something cold, like a suspicion that I had been manipulated. Maybe he greets all visitors this way, but after giving jailhouse interviews for 22 years I thought he must have known why she was there with her lights and camera.

As I left the gates and razor wire of the Terrell Unit, I wondered which version of Johnnny Paul Penry to believe: the sweet and tormented retarded man who didn’t understand why he was in prison or the manipulative psychopathic killer.

PROSECUTORS SAY THAT JOHNNY PAUL PENRY ATTACKED AT LEAST TWO OTHER women before he killed Carpenter. In 1976 he broke into the house of Julia Armitage in Goodrich, Texas, and tried to rape her, but Armitage screamed and Penry ran off. In a statement provided by the police, Penry is quoted as saying, “I went to the house to get a piece and some money.” For reasons that are not clear, he was never charged for this alleged attack.

In February 1977 Penry slipped into the front seat of Di,ma Koch’s car in downtown Livingston. He told her that his brother had been in an accident and persuaded her to give him a ride to a back road. She grew nervous, but when she reached for her CB radio she discovered that the microphone cord had been cut. According to Koch’s testimony, Penry pulled out a switchblade and forced her down a dirt road. He raped her there and told her that if she was good he wouldn’t hurt her. After the assault he got the car stuck and they had to walk. 1\.vo hunters in a pickup offered them a lift. Penry and Koch climbed into the truck’s bed, and when the driver stopped at a convenience store Koch began screaming. The hunters held Penry at bay with a shotgun until sheriff’s deputies arrested him.

When I asked him about this incident, Penry insisted “that was something I didn’t really do.” Then he said, “She wanted it. But her mother made her testify against me.”

In any event, Penry pleaded guilty to rape and was sentenced to five years in prison. He served about half his sentence and was released on parole in August 1979. He was 23. He returned to Livingston, where he quickly found a job as a day laborer for Harold Stubblefield, an appliance dealer. In mid-October he helped deliver a stove to the home of Pamela and Bruce Carpenter.

Pamela Moseley Carpenter was a vivacious, slim woman with long, straight brown hair. At 22 she didn’t have kids yet, but she showered her nieces with attention, she devoted a lot of time to the Central Baptist Church, and she loved to water-ski. “She was beautiful, full of spunk, a real go-getter,” recalls Bruce. The couple met at Livingston High School, got married, and then moved in Houston for two and a half years. After their apartment was robbed they decided to return to their quiet hometown, which was considered so safe that most people never locked their doors. In 1979 Pain and Bruce moved into a house owned by Pain’s parents, and “life was really going good,” says Bruce, his voice cracking.

On the morning of October 25 Pam Carpenter was at home making Halloween costumes and decorations. Sometime around 9 a.m. her mother called and asked her to join a prayer breakfast. Carpenter said she’d rather finish her project but would meet her mother for shopping at Wal-Mart and lunch.

At about 10 a.in. one of Carpenter’s best friends, Cindy Peters, got a phone call: “This is Pam” said a strained voice that Cindy didn’t recognize at first. “I have been stabbed and raped. Help me, and hurry.”

P£NRY LATER TOLD INVESTIGATORS THAT AFTER delivering Pain Carpenter’s stove he had often thought of her. On October 25 he had seen a woman in town who had reminded him of her; he started to think about her some more. “He told us, ‘I was going to get the money and get me some,”‘ says Joe Price, the district attorney who has prosecuted Penry since 1979.

Penry bicycled over to Carpenter’s house n a quiet tree-shaded street near the high school. I he later told authorities that he knocked on the screen door and asked if the new stove was working. Carpenter said it worked fine. Then he forced his way inside and grabbed her. She screamed and managed to knock a pocketknife out of his hand. They struggled, and Penry slapped her face and threatened to cut her throat. When he turned, Carpenter grabbed the orange handled scissors she’d been using to make paper jack-o’-lanterns and stabbed Penry in the upper back. He knocked the scissors away and dragged her into the bedroom. Frantic, Carpenter tried to get her terrier to bite the attacker. Penry kicked the dog under the bed. Carpenter was lying on the floor. He told her to remove her clothes, and when she refused he stomped her very hard with his big brown work boots.

“She had a perfect heel print on her side, below her rib cage, where he’d stomped her,” says Price. “It ruptured her kidney. She had massive internal bleeding.”

According to his confession, Penry raped her on the bedroom floor. Then he picked up the orange-handled scissors, sat on her stomach, and said something like, “I love you, and l hate to do this. but I have to kill you so you won’t squeal on me.” Carpenter didn’t say a word. He raised the scissors over his head and plunged them into her chest. The blades missed her heart but punctured her lung, which collapsed. “He thought that would kill her instantly,” says Price. “But she sat up and pulled then, scissors right out like it was easy. Well that scared him, and he ran out of the house.” Then he biked home.

Carpenter managed to drag herself over to a telephone. She called Cindy Peters and then she called an ambulance.

Livingston police officer Edgar Paige arrived to find Carpenter “with blood bubbling from her mouth.” She managed to describe her attacker: He wore glasses and blue jeans and a red plaid shirt.

Carpenter was rushed to the Livingston hospital, where Corky Cochran. the local ambulance driver and feedstore owner, continued to ask questions about the attacker and broadcast her answers over the police radio.

Sheriff’s Deputy Billy Ray Nelson heard the description and couldn’t imagine anyone from Livingston committing such a crime; nothing like that had ever happened there before. He drove around, looking for a hitch hiker or a vagrant. Then he thought of Penry, whom he knew from around town. (Julia Armitage, whom Penry allegedly attacked in 1976, is Nelson’s sister.) Nelson radioed the hospital: “Did the suspect have extremely dark hair?” “Yes,” came the reply.

Nelson drove up the hill to Penry’s house and knocked on the door. Penry came out wearing work boots and jeans but no shirt. He had a radio tuned to the local news station. playing very loudly. ”What you want?” he shouted.

Penry was sweaty, as if he’d been working out, Nelson recalls, and he seemed hyper. “He was in a different state,” says Nelson. “Previously he’d always want to come up and talk to me. Now he backed into the bedroom and wouldn’t turn his back to me.”

When Nelson asked Penry where he’d been, Penry said he’d been home all morning. Then he said he’d been riding his bike. Nelson asked him to come down to the police station, and Penry agreed. I he put on a shirt, and as they walked out to the car Nelson noticed a bloody spot on Penry’s back. Penry explained that he’d fallen off his hike onto a stick. Nelson hadn’t heard about the scissors yet and let the comment pass.

At the police station they met Price and his investigator, Ted Everin. They all drove to the Carpenter house, and while Price and Everitt went inside, Penry sat in the patrol car, “watching us real inquisitive-like, real squirmy,” Nelson recalls.

Nelson walked around the house looking for evidence, and Penry kept calling to him, “Billy, come here! I want to talk to you!”

“Shush,” Nelson said. “Be quiet.”

“No! No!” Penry shouted. “Come here!” Then: “I done it.”

Nelson says he almost had a heart attack when he heard those words. He remembers the moment with absolute clarity.

“I want to tell you about it,” Penry insisted.

The lawmen read Penry his Miranda rights, then brought him into the house, where, they say, he willingly walked them through the rape and murder of Pam Carpenter. Back at his house, Penry led them to his red plaid shirt. It was in the washing machine; it had two holes in the upper back and was covered with blood.

At the hospital, emergency room doctors treated the stab wound in Carpenter’s chest, unaware of her crushed kidney. A Life Flight helicopter was circling overhead, preparing to airlift her to Houston. The doctors thought they had her stabilized, but when they inserted a catheter the damaged kidney hemorrhaged and Carpenter went into shock and died in a flood of her own blood. The blood washed away any semen there might have been, so no usable DNA evidence was recovered.

Even so, at Penry’s first trial, in 1979, it took the jury only two and a half hours to find him guilty of the rape and murder of Pam Carpenter.

“Penry changed the town of Livingston,” says Lee Hon, who was in the eighth grade at the time and is now an assistant district attorney working on the case. “From then on everyone started to lock their doors.”

JOHNNY PAUL PENRY’S PROBLEMS STARTED ON May 5, 1956, when he came into the world in a difficult breech birth. While his mother Shirley abused all four of her kids, she reserved her most venomous rage for Johnny Paul, the second of her children, because she believed he was illegitimate.

“I used to say. ‘Momma, I love you.’ but she’d say, ‘Shut up, I don’t want to hear it,’ ” Penry recalls, frowning. “She was a little bit overboard with the abuse. It was horrible, horrible.” In a monotone he recounts, “She threatened to cut off my penis. She whupped me with a baseball bat and a big old belt buckle. She burned me real bad on a hot water heater. Tried to drown me in the bathtub …. She pad locked me in my room and covered up the windows with plywood. The ‘buse kept going on and on, stronger and stronger. She bit my heels, gouged out my eyes with her nails. Why? I always wonder why my momma treats me like this …. It’s like a scar deep on my brain.”

Shirley Penry, who died of cancer in 1980, spent time in mental institutions, was suicidal, and drank heavily. “She was a very sick woman,” affirms Penry’s sister Belinda. “And she saw her momma commit suicide by drinking rat poison.”

Penry’s father John worked several jobs and was hardly ever at home. He has since remarried and suffered a stroke, and he reportedly no longer communicates withhis children. The eldest daughter, Trudy Ross, lives in Livingston; Belinda Gonzales was once arrested for burglary and now lives in Houston; and son Jesse is serving a 10-year sentence in an Arizona prison for child molestation.

At the 1979 Carpenter murder trial Shirley testified that she did not abuse Johnny Paul. But Belinda vouches for her brother and says she saw her mother “making him eat his own feces out of his pants. I’ll never forget that.”

A babysitter testified about the burns she saw on Penry’s back when he was two: “She had him in the kitchen sink giving him a bath, and he supposedly turned the water on. But the burns were down his backside, and it didn’t seem logical.” A neighbor testified that she heard “terrified screams” coming from the Penry house, and when another neighbor called a child welfare agency, the Penry’s moved away.

In 1962 Penry attended first grade at an elementary school in Bacliff, Texas. After only a few days he got into trouble for climbing a flagpole and refusing to come down. After scoring 60 on an IQ test he was placed in classes for the retarded and then taken out of school by his parents. “Momma just locked him in his room and left him,” Belinda says. “Sometimes we’d let him out, feed him, get him some sunshine. If she caught him out we’d all get beat.”

At me age of 12, Penry was placed in the Mexia State School for the mentally retarded, where he stayed for about three years. The school’s intake summary reads, “Both parents were rigid when parting withsubject and showed no affection. The mother did not say anything to subject, but hurriedly went to the car, crying and sobbing aloud for a few seconds. I got the impression that she felt this was expected of her.” When his wards at Mexia gave Penry a haircut, they noticed that the boy’s scalp was covered with scars. He said they were from the cuts made by a large belt buckle that his mother whipped him with.

John and Shirley Penry separated in 1971. Shirley moved to Humble, Texas, and John and the kids relocated to Livingston. In December of that year, John arranged for Johnny Paul’s release from Mexia. “Daddy felt like he should be with fanilly,” says Belinda. “We tried to teach him how to read and write at home.”

During the next six years, Penry was twice committed to state mental institutions and was accused of a number of offenses, including fighting, sexual abuse. and arson. In 1976, when he was 20, he allegedly attacked Julia Armitage. He had turned down a dark alley fro1n which he would never emerge.

THERE WERE NO WITNESSES TO THE CARPENTER murder, so it has not been definitively proven that Penry was responsible. But Penry’s lawyers are arguing the fairness of his trial rather than his innocence. “Neither myself or any person working to stop the execution of Mr. Penry in any way minimizes the tragic crime that lies at the heart of this case,” writes lawyer Bob Smith. “The question … however, is the appropriate punishment.”

One of the central questions is just how culpable Penry actually is. If a defendant can demonstrate that he did not know right from wrong when committing a crime, he is judged insane and is automatically exempt fronm the death penalty. Retardation is different. Experts consider a person retarded if he has an IQ of less than 70. State authorities have tested Penry’s IQ as low as 51 and as high as 63. Prosecutors, however, contend that Penry has scored as high as 72 on certain parts of the IQ rest, which might suggest he sabotaged his performance.

“There is no doubt he is retarded,” says James Ellis, a leading expert on mental retardation and the death penalty at the University of Ne1v Mexico School of law who wrote the amicus brief for Penry’s Supreme Court hearing. “He puts up a good front. He wants to appear to know more than he actually does.”

But the prosecutors and the family of Pam Carpenter do not believe that Penry is retarded, and they doubt he was abused as badly as he claims. They want him put to death as quickly as possible.

“Penry is the wrong poster child for the issue of mental retardation,” says Ellen May, who has a child with learning disabilities and has coached retarded children. “When the media come around, he starts with the stuttering and baby talk, but he’s just faking to avoid the consequences of his actions. He must face them. He is not a sweet little boy.”

“He knew enough to plan the crime and the getaway. He knows what he did was wrong,” says Price. “He’s a cold-blooded killer. And every jury that has ever considered the facts has agreed with that unanimously.”

Mark Moseley, one of Carpenter’s three brothers and a former all-pro placekicker for the NFL’s Washington Redskins, says, “I could have used my sports celebrity to say more about our side of the case. but we wanted to let justice run its course. Instead it’s dragged on and on, with no sense of closure. All the special interests are jumping in-mostly to promote themselves. It’s a farce. And it’s just torture for my parents.”

Jack and Rossie Moseley have been crushed by the toss of their only daughter. Rossie writes, “There has never been a night that I didn’t go to bed and cry for her pain …. I envy other mothers with daughters. I don’t mean to be jealous, but it is an aching feeling …. I bought her a leather jacket for her birthday, and her first time to wear it was in her casket.” After Carpenter’s murder the family moved from Livingston to a farm; her parents’ marriage almost foundered. “It’s been real, real hard,” says Jack in a hoarse whisper. “‘We’ve waited so long for justice, and I’d hate to go to the grave and him still alive …. I’m a firm believer in the rope they used in the old frontier days as a deterrent to crime. When they used that, it had a real quick effect on people.”

Carpenter’s husband Bruce has been through two failed marriages since her death. Choking back tears, he says, “I just wonder what life would’ve been like if this hadn’t happened.”

TODAY IOIINNY PAUL PENRY HAS SUPPORTERS around the world, some of whom insist that he is innocent.

“The problem is, it’s very easy to get Johnny to confess to almost anything,” says Father Walsh. “He had delivered a stove to [the Carpenter] house, and his fingerprints could have been left over. There is at least the possibility of his innocence.”

‘Il personally do not believe his confession,” says John Wright, the Texas lawyer who has defended Penry for more than 20 years. ”Penry had no advocate at the scene of the crime, so you have to take the sheriff’s word. They asked him yes/no questions. That is not the way to get a reliable statement from a mentally retarded person.”

Penry’s sister Belinda insists he was framed: “The Livingston police railroaded him.”

Others say Penry’s guilt or innocence is not the point.

”The Supreme Court has established that only the most blameworthy of convicted murderers can be executed. So how can those who have the lowest level of understanding fit that criterion?” asks Ruth Luckasson, professor of special education at the University of New Mexico. “What is the purpose of executing him? Is it rehabilitation? The mentally retarded can’t be rehabilitated. Is it to set an example? Executing someone with an extremely low IQ will not [change the behavior] of those with low IQs–0r those with high IQs. So what’s left? Some kind of extremely simplistic retribution? That is not permissible under the U.S. Constitution. It is illogical to make the jump from finding Penry guilty to executing him.”

“Johnny is a child trapped in a man’s body, as he was the day he committed the crime,” says Bonnie Caraway, a pen pal who has created a pro-Penry website .. “Executing someone who doesn’t know what he’s doing is the greatest sin Texas could ever commit.”

THE FIRST TIME PENRY’S CASE WENT BEFORE THE Supreme Court, in 1989, his lawyers not only challenged Texas law, they also claimed that executing the retarded is unconstitutional. Writing the majority opinion, which ruled against unconstitutionality, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor said that there was no “national consensus” about the issue. Instead the court determined that Penry deserved a new trial because the Texas jury had not been told that he might be retarded. That ruling, now referred to as the “Penry instruction,” forced Texas to rewrite its jury instruction in capital cases. Ironically, Penry was not a beneficiary. By the time he was retried, the new jury rules were not yet in place; his attorneys used this point to convince the Supreme Court to hear his case a second time.

In the meantime, the context of the case has shifted dramatically. In 1989 only two states (Maryland and Georgia) of the 37 with the death penalty banned executing the retarded. Today 13 of the 38 states with the death penalty prohibit such executions. as does the federal government. Combined with the 12 states that don’t have the death penalty, that means half the nation now forbids executing the retarded. Even conservatives are lining up against the practice. Florida governor Jeb Bush is opposed to executing the mentally retarded. George Ryan, the Republican governor of Illinois, bas put a moratorium on all executions. And a number of condemned prisoners-McCarver in North Carolina and others in Mississippi, Virginia, and Maryland-have been granted temporary reprieves until the Supreme Court issues its decision on Penry in June.

In April the Texas legislature took a new look al the state’s policy on capital punishment. At this writing, the House had passed a bill banning executing the retarded and sent it to the Senate. (If the bill becomes law it will not be retroactive and thus not affect Penry.) Governor Rick Perry remained neutral on the debate, saying that Texas should take its cue from the Supreme Court.

ON THE COLD, BLUSTERY MORNING OF MARCH 27, the white Supreme Court building stood out sharply against a blue sky. Inside the temperature was considerably warmer as the justices pelted the lawyers with tough questions. This time Penry’s attorneys had decided to bypass the larger issues and focus instead on two legalistic points: whether Texas’s new jury instruction is still flawed and whether a state psychiatrist’s report violated Penry’s right against self-incrimination.

O’Connor called the jury instruction “awkward, to say the least.” But Justice Antonin Scalia maintained that it was perfectly clear: “We assume that even if the defendant is mentally deficient, the jury is not.”

Although no one mentioned the McCarver case, it was clearly on everyone’s mind. For years organizations from around the world have been urging the court to rule on the issue of executing the retarded. The American Bar Association, opposed to such executions, notes that only the U.S. and Kyrgyzstan carry them out. The European Union has outlawed them entirely.

The effect of the Mccarver case on Penry is unclear. “I’m no constitutional legal scholar,” says Joe Price, “but the two cases are arguing different points, so I don’t see how they’re related.” Bob Smith disagrees: “[McCarver] certainly benefits Penry.”

THE SUBJECT OF DEATH REMAINS ABSTRACT FOR THE man at the center of the debate. Johnny Paul Penry seems more afraid of images of death – the gurney, in particular-than of death itself. “I have heard that the injection of a drug makes your eyes roll back in your head,” he says in wonder. “They put a needle in your arm and put you to sleep and you don’t wake up. But I think there’s a little bit more to it than that.” He’s aware that his case is important, and he understands what is at stake. “I’ve been over [to the death house] two times now. I’m pretty damn lucky to get a stay. I’ve outlasted a lot of those guys. I’m a survivor.”

The Moseley family, meanwhile, struggles with conflicting impulses. “As a Christian I believe it is our responsibility to forgive those who harm us,” says Ellen May. “I have been trying to forgive Penry in my heart of hearts. But it’s hard. For a long time I didn’t. Now I truly believe that one day he will walk through the gates of Heaven and my Aunt Pam will greet him with open arms.”